APPROACHES

Graphic events:

Case Study 4 – Tory Bingo

1. THE POSTER

#ToryBingo represents another ‘graphic event’. It shares some characteristics with MyDavidCameron, but also has some critical distinctions. Rather than being collated on a single website, in this Case, we find the posters distributed on the social networking platform Twitter. Here, the pace of exchange is accelerated, public engagement is extended, and dissemination takes a complex, dialogic form. While continuing to observe the creation of remakes, we learn that the gestures of revision are minimised and quickened. Digital picture-editing skills become (even) less important, superseded by the visual articulacy and swift wit of combining text with image. These facets of divergence, subtly alter how we conceptualise the ‘event’, and change the way we set about collecting it.

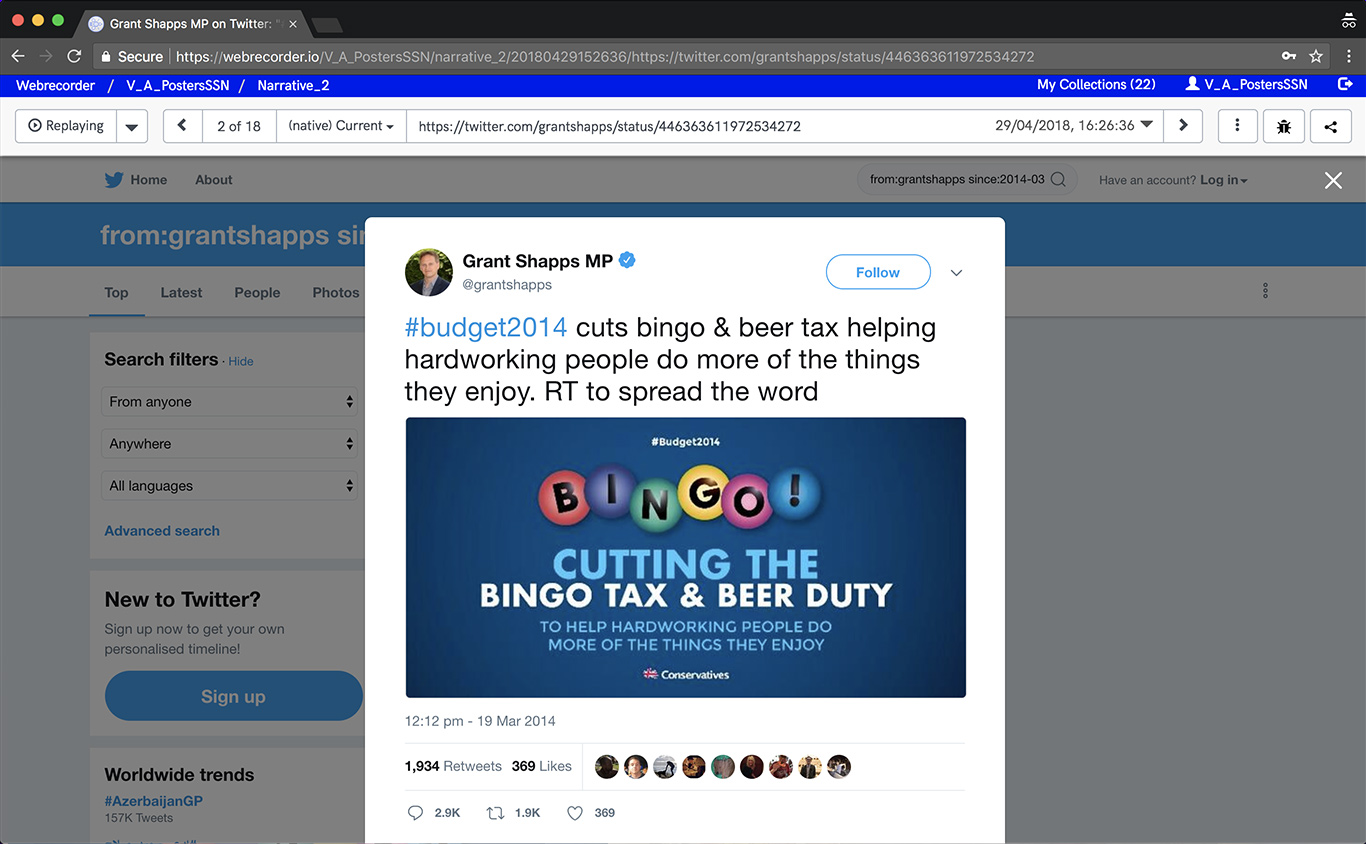

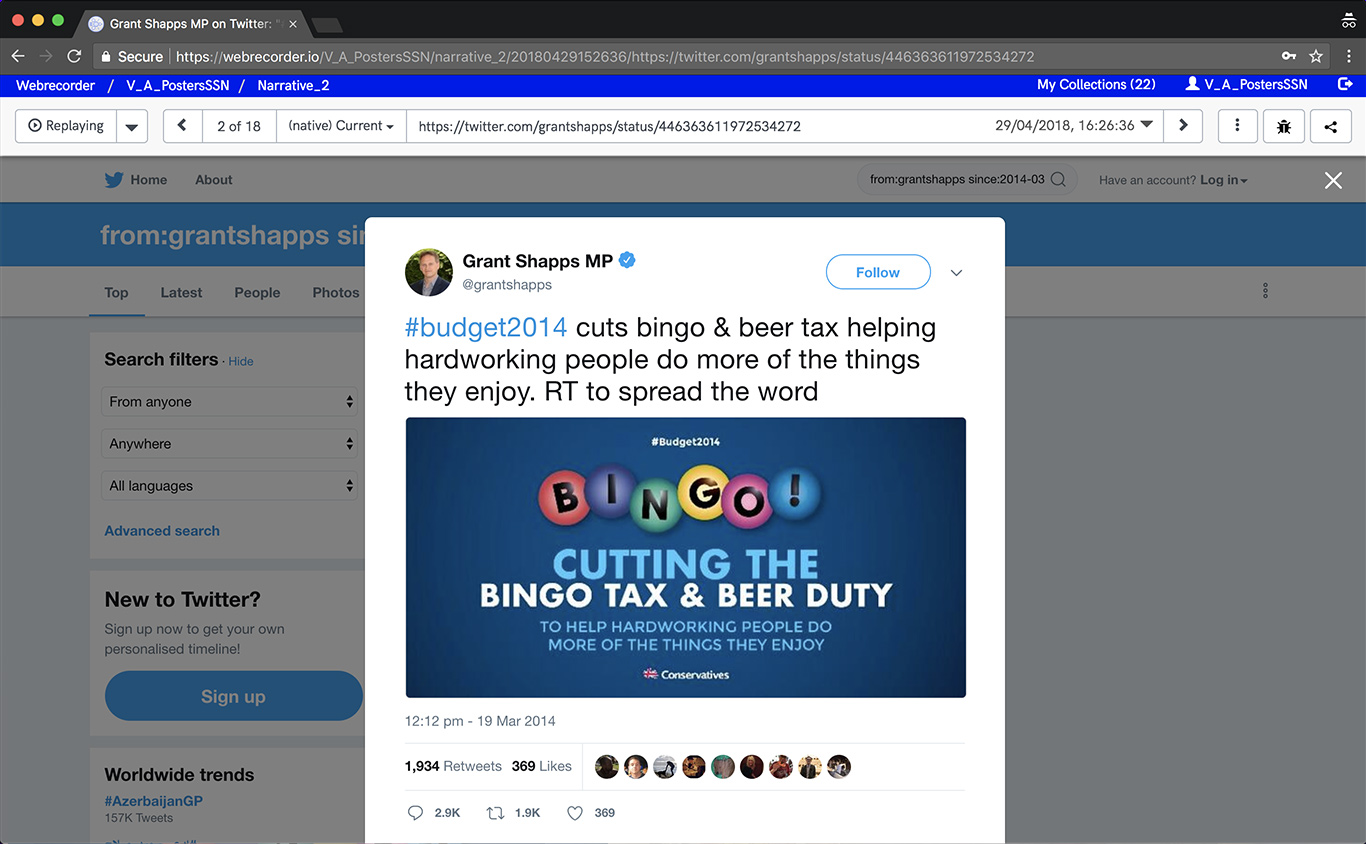

The origin of this meme is a graphical advertisement, which was released ahead of the Coalition Government’s spring Budget of 2014 as an infographic, ‘tweeted’ by the then Conservative Party Chairman, Grant Shapps (figure 4.1). It celebrated a planned reduction of alcohol duty and gambling tax, controversially claiming that these concessions would “help hardworking people do more of the things they enjoy” — a message that was broadly viewed as classist and patronising. Offline, the poster attracted National headlines and ignited a political backlash. Online it stimulated a social media revolt.

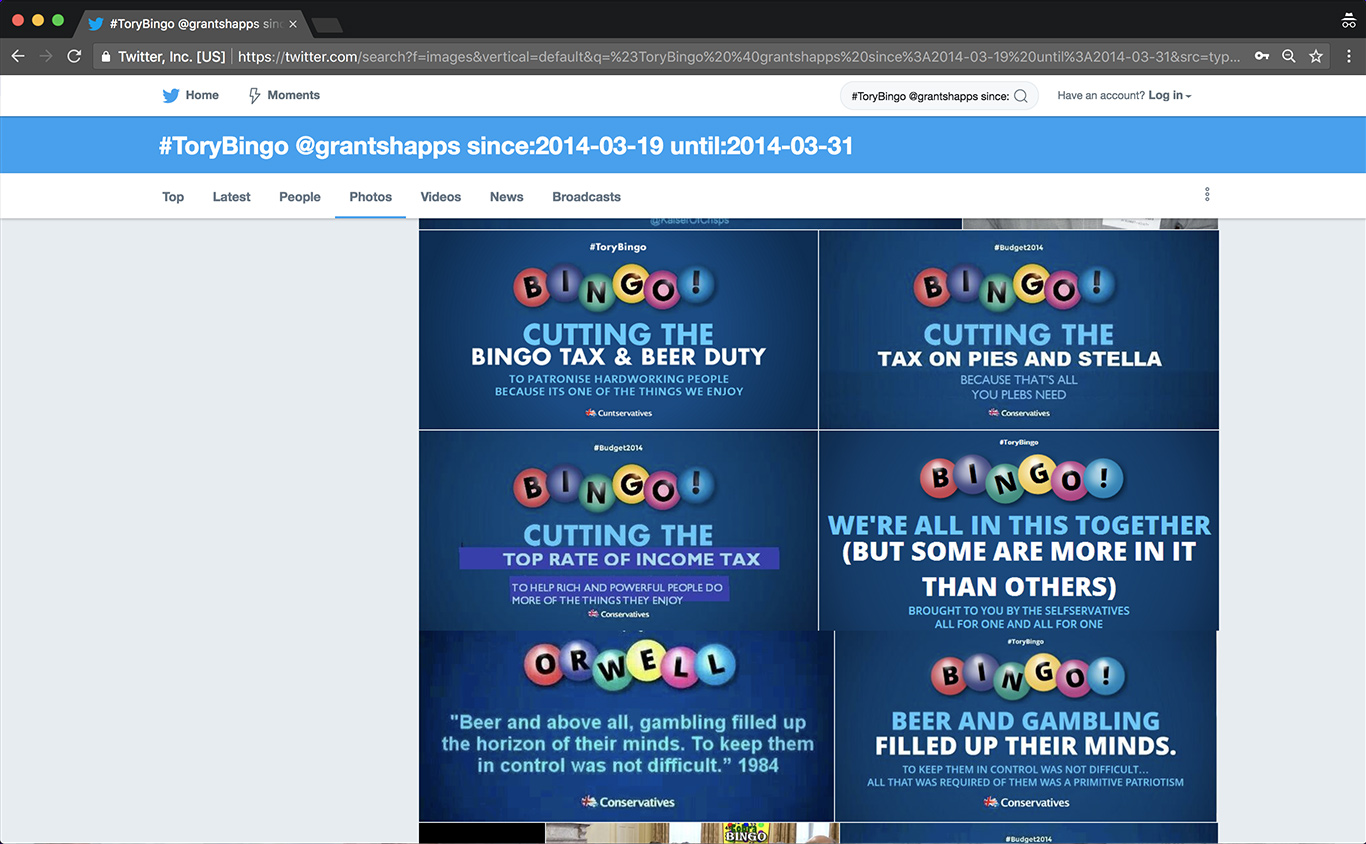

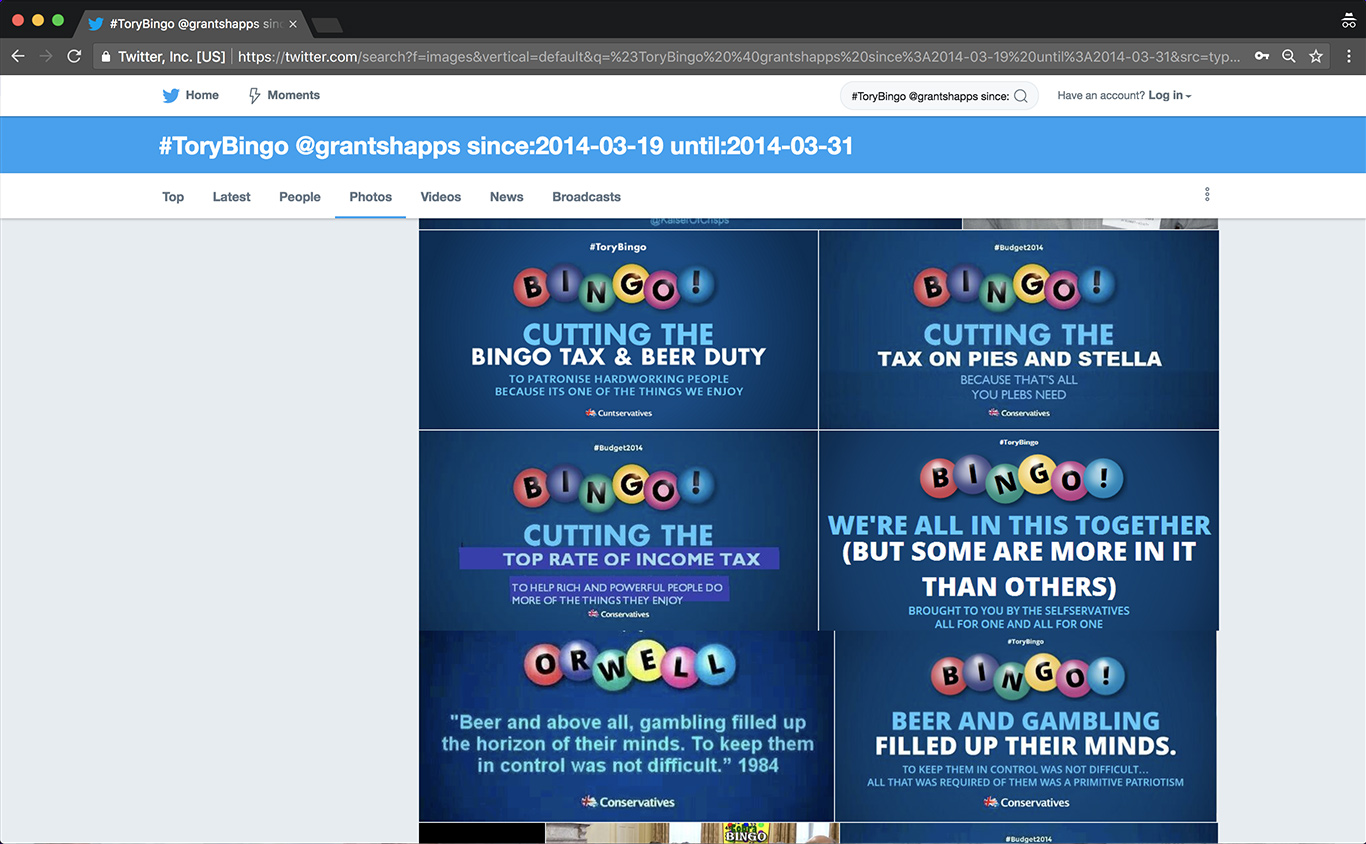

As in the previous Case Study, we observe how a poster published online has a different vulnerability to defacement than traditional printed graphics. Not only because in digital form, the simple graphical components of the poster can be easily dismantled, but also because social cultures in this realm facilitate and fuel collective activism. Online personas provide users with a cloak of anonymity, while amassed small actions gain momentum and can be transformed into powerful surges of opposition. In this example, what ensued was a deluge of sardonic re-makes, which used alternative wordings to rebuke and ridicule the original.

In terms of design, no single example is particularly interesting, but in aggregate these visual parodies vividly reveal how social media has augmented the way publics can express their political dissent, and how spaces like Twitter are changing the nature of graphic communication.

Initially conceived as an internet-based short messaging platform, statements and replies on Twitter which include images, stand out from predominantly textual lists (or ‘feeds’) of Tweets. One of the platform’s defining features is that it facilitates conversation-like interactions comprised of chained statements and replies, interposed by regular repetitions (known as Re-Tweets). As poster curators, we are particularly interested in what happens when these interlinked exchanges become visual (figure 4.2). The conversational structure of dialogues on the platform give us new opportunities to retrace the path of an image’s dissemination, investigate its mutations, and plot engagement over time.

We observe that when it comes to what makes a poster ripe for appropriation, graphic banality eclipses originality. #ToryBingo provides evidence that the more humble the design formula, the simpler it becomes to mimic. This image lent itself to appropriation because when reduced to its basic elements, it remained recognisable — even when those components were substituted. This meme’s power derives from its identifiability over cumulative encounters. Our visual knowledge/memory of its previous iterations become mixed with each new version we see. The humour of the alternative messages are all the more effective because we have read their variants. Each meme is an associative, implicit, knowing reference to its predecessors — an interplay which cannot be represented by a singular image file, displaced from this context. Meaningful collecting of these graphic objects is therefore contingent upon capturing plural iterations, and revealing the socio-cultural domain within which they evolved.

#ToryBingo, enables us to see how ‘graphic events’ in the era of social media develop a more complex structure. In Case Study 3, we noted that the MyDavidCameron memes were collated on a website, while here, we find instead that remakes are dispersed on Twitter. To collect this ‘event’, we must first investigate the site of the poster’s distribution, then find ways of aggregating a sample of its variants ourselves. In this sphere, we observe that the posters are embedded within extended comments threads (figure 4.3). An interesting affordance of interactions on Twitter is that when one Tweet refers to another (either by replying, re-tweeting, or quoting), the source Tweet becomes connected to the referrer. Each component Tweet in these exchanges can be expanded, and shown in position within the conversation’s thread. This characteristic of the environment provides poster curators with an unusual scope for insight: as we retrace the steps of an image’s exchange, we can also ‘listen in’ on the dialogue that surrounds it.

Unpacking Tweets in their native context, we realise there is renewed potential for curatorial analysis and interpretation of the public’s encounter with posters. Readily available metadata imprinted upon each Tweet, supply us with rich and specific information.

For example, we know exactly when an image was published, and we are provided with a gauge of how many people saw it — via tallies which count the numbers of those who responded, and those who went on to share it among their own network. Equally, we can investigate this data to chart the pace and duration of the meme’s liveness — to discover whether its virality developed gradually or rapidly, was sustained or brief.

We have been thinking of social networking platforms as new realms of public space, and have found it productive to consider the democratic potential of Twitter, Instagram etc. in relation to the use of available, inexpensive printing materials by activists and voluntary organisations throughout history. People taking up the tools of social media to communicate and distribute their message, is not dissimilar to people making use of available printing materials, or basic reprographic technologies to produce quick and simple posters.

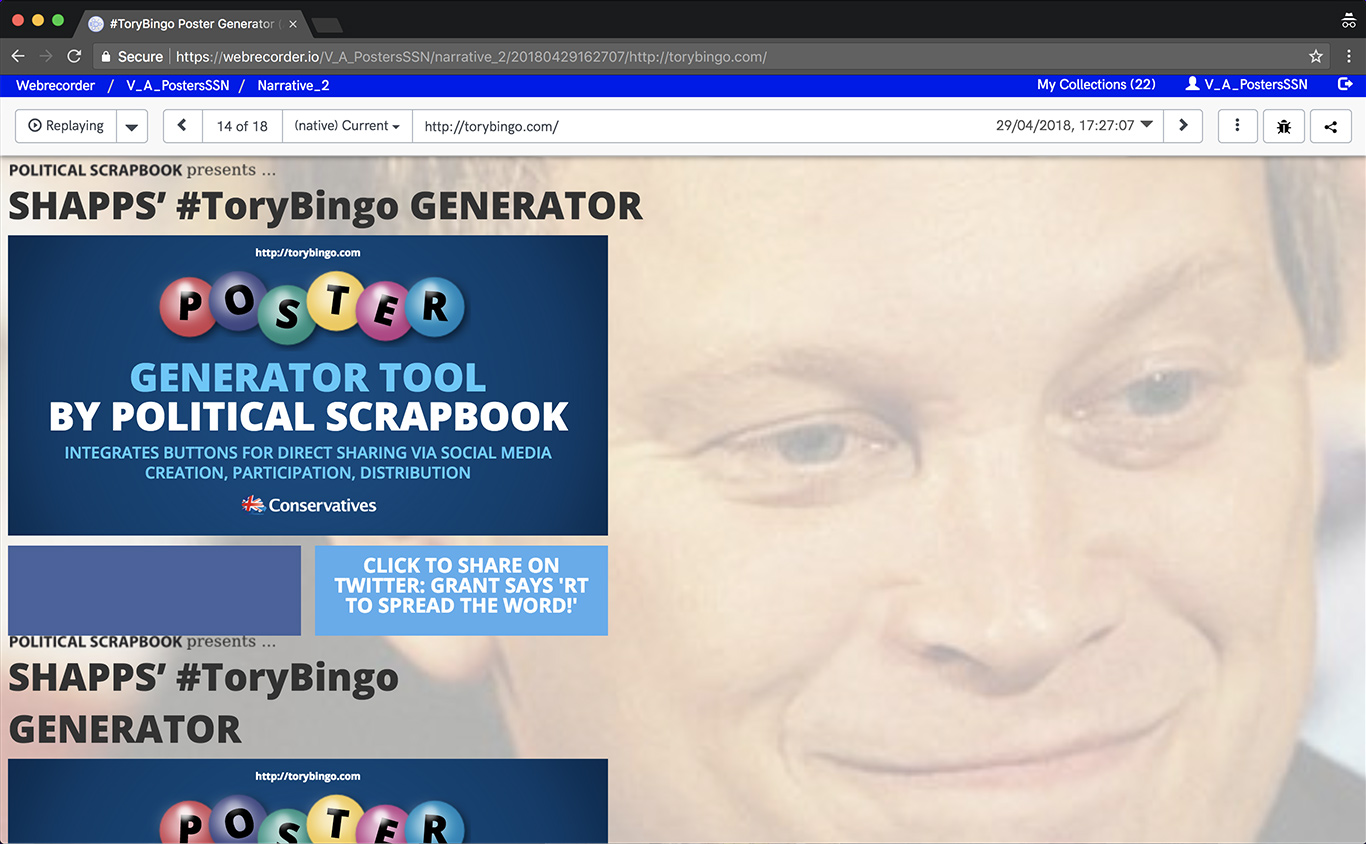

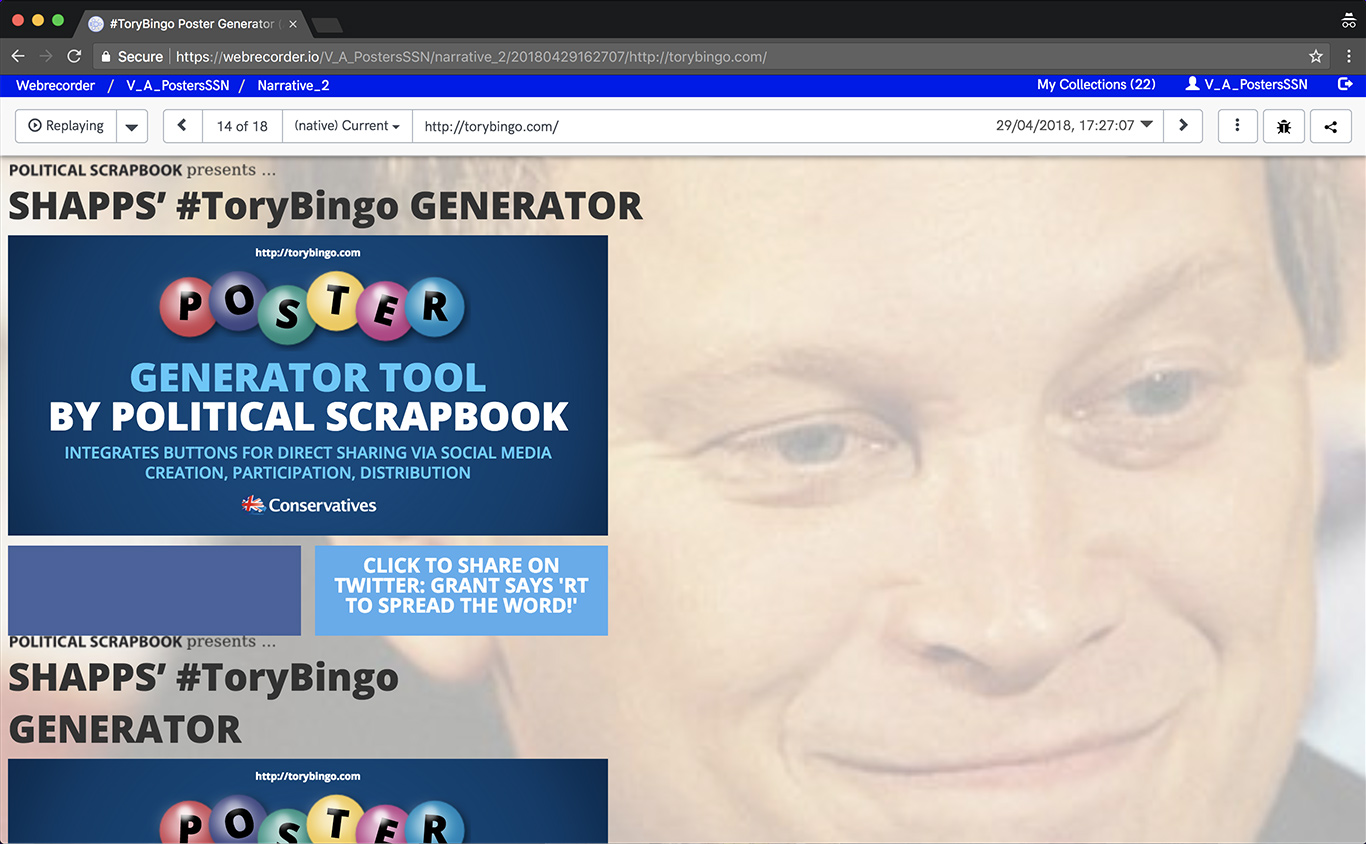

Once again, an online ‘poster generator’ emerged as a key tool used to subvert this image (figure 4.4). Built by the team behind the Political Scrapbook blog, this meme-making tool works in a similar way to the one discussed in Case Study 3. The noteworthy difference is that rather than offering users the option to save or drag-and-drop the poster onto their computer desktop, the #ToryBingo generator site more explicitly integrates buttons for direct sharing via social media. Generators for the social media era, can be thought of at the intersection between instant creation and instant publishing. In this way, the actions of participating and distributing collapse into one.

On Twitter, participation is not limited to poster-making, but includes contributions which commentate, duplicate and propagate the image. While the MyDavidCameron site integrated vote widgets, in the #ToryBingo example, we note that web users are able to engage with what they see in broader range of ways. The Twitter platform can be characterised by the interactive nature of the dialogue it promotes, in which multiple users’ voices coexist, responding to and engaging with each other. A useful analogy; for understanding how fundamentally the Web 2.0 environment has altered our encounter with posters, is to consider online marketing companies who collect social media ‘engagement metrics’ to analyse how users respond to content. In their terms, responses are valued on a sliding-scale, beginning from the user who assumes a passive position (watching), moving towards engagement (voting or ‘Liking’) to being fully engaged in interaction (commenting and replying, creating or sharing). This Case Study example helps us as curators, to comprehend and describe how the action of encountering a poster, has progressed from observing an image to participating in a ‘graphic event’.

2. METHODS OF COLLECTING

In her 2016 report, Preserving Social Media, Digital Preservation Coalition Research Officer Sara Day Thomson writes about the ‘interlinked, conversational’ structure of social media. She observes that it is this, which makes it difficult for traditional web-crawling technology to define the object to preserve. As a curator-operated archiving tool, Webrecorder initiates collecting practice that meets this technical challenge, encouraging us to navigate through the social media environment, and engage in the negotiation of where (and how) to define the ‘graphic event’s’ boundary.

Figure 4.5: Using Twitter’s Advanced Search. Source

Figure 4.5: Using Twitter’s Advanced Search. Source

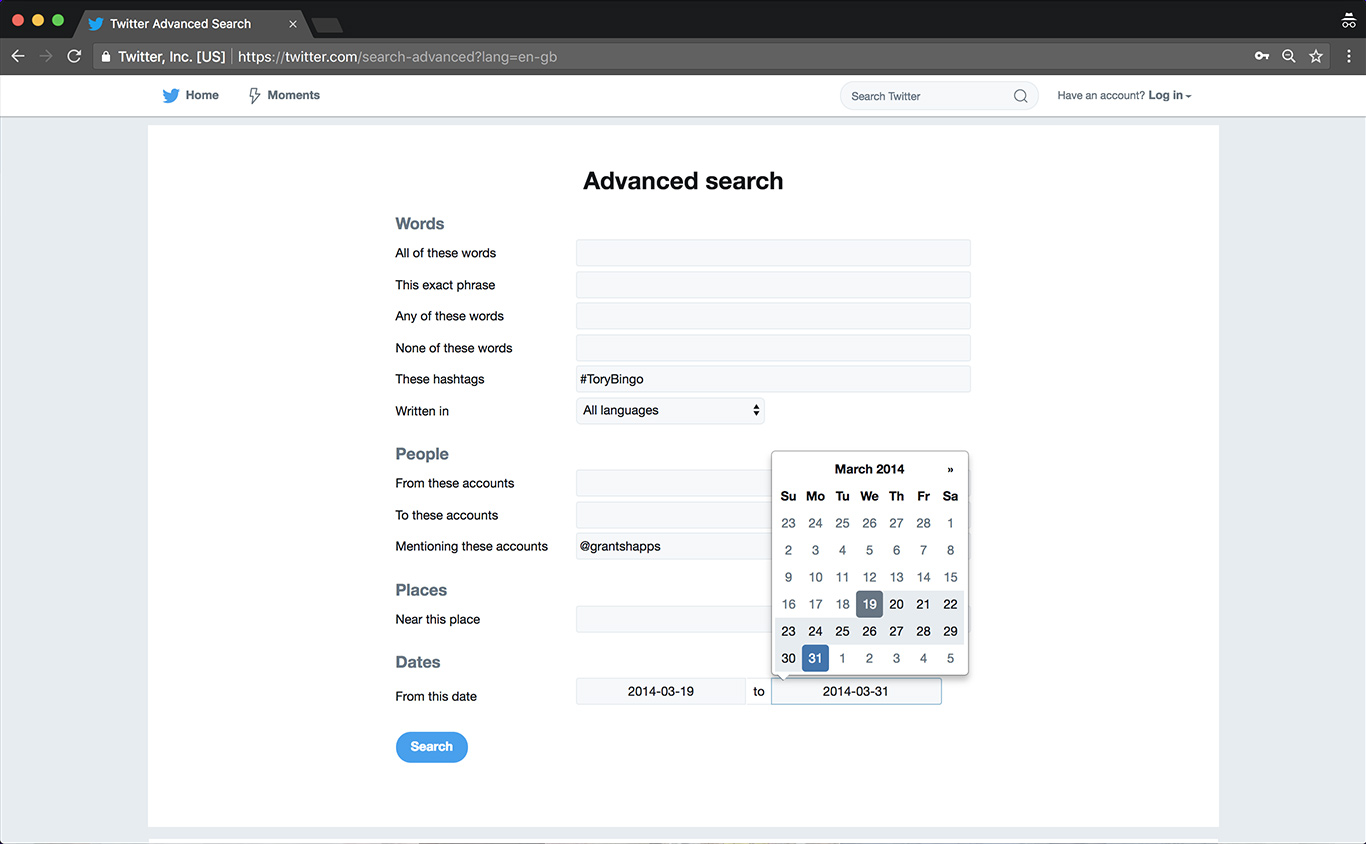

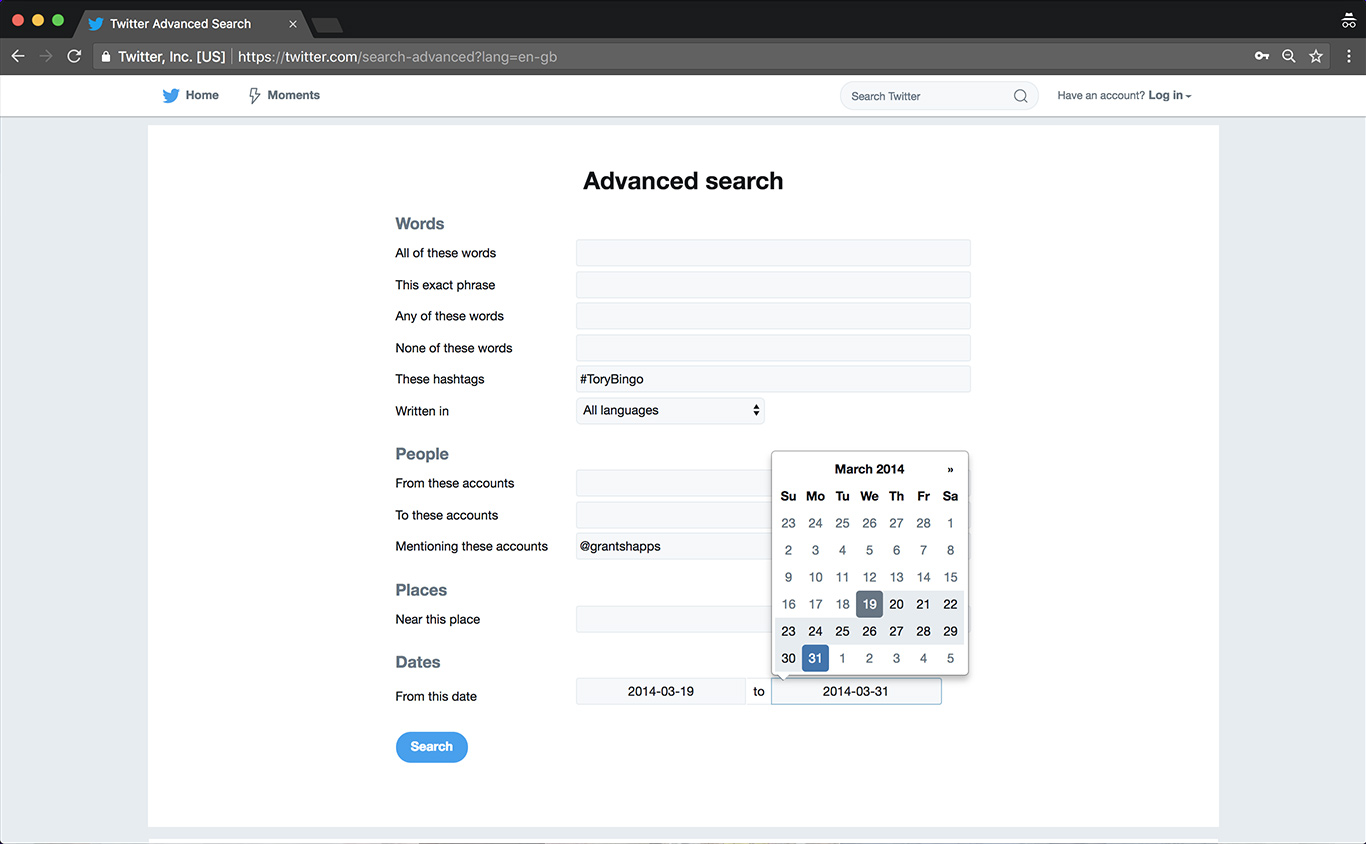

Through Case Study 4, we have explored this problem. The #ToryBingo ‘graphic event’ is dispersed on Twitter. Collecting it involved actively visiting the platform to first identify an entry point from where we could hone in, and then proceeding to perform a sequence of thoughtful, intentional, focused searches in order to aggregate related Tweets and materials. In this instance, we were able to identify a specific trigger Tweet, posted by Shapps on 19th March 2014. We considered this the moment which activated the ‘graphic event’. From here, we set about aggregating the related materials. Direct replies could be found threaded in a conversation extending from this source Tweet. However, many of the subsequent shares which propelled this graphic forward, were Retweets rather than replies, and scores of others did not directly either reply to, or mention Shapp’s account handle. It was therefore necessary to adapt our search terms, and run a sequence of variant searches in order to retrieve a more comprehensive range of the remakes. We began with using Shapp’s own account handle as our anchor. Using Twitter’s advanced search function, it was possible to specify a search for Tweets originating from, replying to, or mentioning a particular person. Meanwhile, we experimented with specifying various date ranges beginning from 19th March (figure 4.5). When search results have been aggregated, it is possible to apply additional filters, and we opted to sift by post type (figure 4.6). We agreed to collect the combined textual/graphical Tweets delivered by each initial search, and then to apply the filter and view only posts which include ‘Photos’ (the term ‘Photos’ is used loosely here, so selecting this tab enables viewing of mean ‘all images’).

Figure 4.6: View of Twitter’s Advanced Search results filtered by ‘post type’ (photos). Source

Figure 4.6: View of Twitter’s Advanced Search results filtered by ‘post type’ (photos). Source

Very quickly after the meme took hold, the hashtag #ToryBingo began to be used. In our collecting tests, we continued our investigations of the capability of Advanced Search, using words. We had noticed several things: that there was a near-immediate ambivalence to the suggested hashtag suggested for use by the infographic, and that more than one hashtag had been initiated. The informality and inconsistency of posts on Twitter, means that hashtags are frequently established but then ignored, or introduced and later changed. Attempting to draw together as much of the relevant content as possible, we resolved to try a set of possible word-based terms, including #Budget2014 (which appeared on the original), #BeerAndBingo (which became commonly used when speaking about the phenomenon) as well as #ToryBingo (by far the most widely adopted and persistently applied of these three hashtags). Again, we tested supplementing these filters with date ranges, and further decreased the breadth of our results by filtering by post type: ‘Photos’. Our combined and varying search strategies reflected our collective recognition that it would not be possible to retrieve all relevant results using any single of criteria. What is helpful both to us as curators, and to an end-user encountering the Webrecording is that advanced search terms are displayed in a bold banner that heads retrieved results. This means that the aggregation presented never purports to be anything other than a sample, retrieved within specific limits. Recognising the ‘graphic event’ on social media as elusive, our aim was to provide a snapshot — but to strive for that sample to be well contextualised so that the ‘event’ retains its complex character, hinting at something larger than we can capture. As with Case Study 3, we supplemented our in situ collecting with a broader means of aggregation from the web using Google Images (for an explanation of our method: see Case Study 3.

Again, we must be cautious of the fact that when we are collecting retrospectively, an inherent temporal incoherence occurs. Embedded tallies of mentions, retweets and favourites reflect activity from the time of posting up until the time of collecting. These metadata aspects cannot be responsive to an advanced search within a date range, for example. Another important note is that visually and technically, both the design of the browser environment and the Twitter platform’s interface have changed since March 2014. While the Tweets posted are retrievable1 they are only retrievable within the current contextual surroundings, alongside current Trending topics, and presented within Twitter’s current interface.

Curatorial orientation within Web 2.0 depends upon agility to perform in-platform searches which collate posts associated by #hashtag, originating from particular @account handles, or including common @mentions. To collect from these spaces, we must develop an adeptness to exploit native tools which narrow criteria, filter and nuance the yield.

Mirroring the poster’s shift, the contemporary graphics curator’s role also needs to alter: a central new responsibility is to be an active web user. Only by adopting an embedded vantage point will we be able to develop first-hand insight of individuals/groups who are generating graphics online.

Knowledge of which hashtags are being appended, which user accounts are active, which keywords are common will be key to tracing the circulation of poster images, and remaining attentive to the visual dialogue which surrounds them so that we can target ‘graphic events’ for capture and recognise the moments to collect them.

3. ELEMENTS OF THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION

- An assemblage of appropriations within the context of Twitter (WARC) created using Rhizome’s Webrecorder

- An assemblage of appropriations aggregated using Google Images (WARC) created using Rhizome’s Webrecorder

- An online ‘poster generator’ tool (WARC, including static page snapshots) created using Rhizome’s Webrecorder

- A selection of associated online media coverage (WARC) created using Rhizome’s Webrecorder

4. KEY FINDINGS

- Collecting ‘graphic events’ which are distributed on social networking platforms such as Twitter, involves actively searching for and aggregating a group of components.

- Curators need to develop agility within these spaces to be able to navigate and hone strategies for in-platform searching. If we are active web users, we will gain the advantage of an embedded vantage point on contemporary design/circulation activity.

- Social media posts are imprinted with metadata which reveal key contextual detail. With Webrecorder we can collect these objects within their native contexts. This supports future analysis and interpretation of the public’s encounter with posters.

- Retrospective capture can introduce distortion, because metadata tallies reflect cumulative activity, i.e. from the time of posting up until the time of collecting.

Notes

1. If they have not been deleted by the account holder. ↩

Read more about the collecting tools we have used here.